In June, the C.D. Howe Institute released research outlining the impact of pricing regulation on auto insurance in Canada. Their paper, entitled The Price of Over-Regulation and authored by Gherardo Caracciolo, separates the provinces into two groups: the first includes Alberta, Ontario, and the Atlantic Provinces while the second group is made up of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia. Quebec and the territories were excluded from the analysis. Provinces in group one were deemed “more regulated” in terms of their pricing regulations while those in group two were the de facto “less regulated” provinces. Caracciolo, after running some analysis around the yearly precent change in premiums and the yearly percent change in claims found that insurers in the second group of provinces raise yearly premiums at a rate more in line to the yearly increase in claim costs. The conclusion of the paper is that the pricing regulations of the provinces in group two allow the auto insurance providers to be more flexible and limit market inefficiencies. The background, data, and story presented however requires a wider scope to analyse the auto insurance markets in Canada. The paper also makes what we consider an oversimplification, as comparing private and public auto insurance markets within Canada is akin to comparing apples to beef.

Footnote to the reader: This is a limited response to the paper “The Price of Over-Regulation: Assessing the Impact of Rate Controls on Auto Insurance Market Flexibility in Canada”. We used data that we already had on hand. A full replication and extension of Caracciolo’s results would be difficult as it would require the purchase of some of the data used in the original paper. Further, the paper does not go into detail on the exact data definitions, controls, or even number of data points used in their quantitative analysis.

What the report missed about price regulation

The paper focuses on the differences in price regulation across Canada. Specifically, the paper outlines different regulatory frameworks for how firms are allowed to change premiums. The two frameworks observed in Canada are prior approval, and file and use. Prior approval requires any change in a firm’s pricing structure to be approved before it is implemented. File and use on the other hand allows firms to start applying changes as soon as it files those changes with the regulator and then the regulator has a set period of time to confirm or reverse the changes. Comparing these frameworks of prior approval and file and use is where the paper stops, however there are two other elements to pricing regulation in auto insurance. On top of the regulatory framework there is the speed and the frequency of which changes are allowed to be made, as well as the profit or return on capital limit which provides an upper bound to premiums. We will go through all three to show how they shape the regulatory environment in Canada’s provinces.

First, a correction: in The Price of Over-Regulation, Caracciolo describes the various rate approval frameworks that exist in Canada but errs in his description of the regulatory framework in Alberta. In Appendix B in the paper breaks down the regulatory framework in each province and for Alberta claims: “In Alberta, insurers can immediately implement rate changes up to 5% after filing with the Alberta Insurance Rate Board (AIRB), as long as the rates meet regulatory standards”. This statement is incorrect. Alberta is entirely a Prior Approval province, that is any price change must be approved before it can go into effect. Alberta’s Insurance Act, and specifically the Automobile Insurance Premiums Regulation states as such in Section 2.1: “No insurer may charge or collect a premium for basic coverage or additional coverage unless the insurer’s rating program with respect to that coverage has been approved in accordance with this Regulation”. We also reached out to the AIRB and they confirmed both that Alberta requires prior approval for all premium changes as the regulation states and that the statement made in the C. D. Howe paper was incorrect. On the surface, this correction improves the paper’s position, as Alberta is even more regulated than originally claimed. As we shall see however, understanding the regulatory framework in each province provides only a very narrow perspective of the entire regulatory pricing system for auto insurance in Canada.

The second element of premium regulation is the amount of time from filing to approval and how often a firm files, which can directly impact the response time of changes to claims. While auto insurance policies renew every year that does not mean that a firm cannot update their premiums more than once a year. In Ontario there is no real limit to the number of times within a year that a firm can apply to update their premium structure. For example, since the start of 2020 until the time of writing, the Intact Insurance Company has had 22 rate changes approved, or around four a year. Since 2022, Intact has also had 16 rate changes approved in Alberta, again around four a year. All of these changes from Intact in Ontario and Alberta corresponded to either no aggregate changes in total premiums (i.e. the average individual premium change was 0) or a positive aggregate change (average premiums increased). You may ask then that maybe Intact filed more than 22 rate change applications in Ontario since 2020 and the process is being slowed down by denials. However, we have confirmed with the Ontario regulator (the Financial Services Regulatory Authority, or FSRA) that they have only outright denied one rate application of over 2000 across all firms operating in Ontario since 1988. So, we can consider the number of applications to be the same as the number of approvals. After approval, the rate changes go into effect usually within 60 days and are implemented as individual policies come up for renewal. Conversely, Manitoba and Saskatchewan have their public monopolies update premiums exactly once a year. Not four, not even two, just one annual rate adjustment.

The third element of premium regulation, that is by how much firms can change premiums, corresponds to the profit or return on capital limits each provincial government put in place. That is premiums are allowed to be raised up to the point where assuming a certain amount of claims and fixed business expenses, the firm would make a profit equal to X% of premiums. In Ontario this figure is 6%. In Manitoba and Saskatchewan, that number is 0% because the public monopolies have mandates to provide auto insurance at the lowest cost possible, which includes not taking a profit. The profit or return on capital in B.C. is more complicated and would require a separate piece to analyze this part of the pricing regulation. B.C. has had a fully public monopoly and a hybrid system which is further complicated by the fact that the provincial government has mandated at times that the public monopoly be non- or for-profit enterprise. A non-profit public monopoly and a for profit private company have drastically different incentives and goals. A nonprofit would be seeking to limit any increases to premiums instead of increasing them as much as would be profitable like the private company would. Critically as well, a public non-profit would lower premiums or return premiums to consumers when costs fall, whereas if private firm see lower claims than expected they can simply profit the difference and maintain premiums. Finally, the limit on premiums from regulating profit margins is why premiums need to be approved in the first place. By this metric, B.C., Saskatchewan, and Manitoba are the more regulated provinces, not the less regulated ones.

We do not make policy decisions on only 45 data points from 10 years ago

The C. D. Howe paper argues for regulatory changes or reflection on the current rules and a move towards a more nimble framework to help the auto insurance industry provide affordable, accurate premiums. The data from the paper used to make that point however is limited and from a decade ago. For Alberta, Ontario, and the Atlantic Provinces, the years 2011 to 2016 are used, and for B.C., Manitoba, and Saskatchewan the paper uses 2006 to 2016. As the paper uses annual numbers and combines all four Atlantic provinces it means only 51 data points are used for the analysis. It should be noted however that the paper does not provide enough detail to confirm exactly how much data is used. The 51 data points is lowered to 45 since the yearly percent change in premiums and claims is used which requires dropping the first time period for each of the six geographic regions. To continue to build our understanding of an auto insurance industry that collects 10s of billions in premiums annually we need more than 45 data points and specifically a longer time horizon. Then, setting the number of data points aside, the industry has changed quite a bit in the last ten years.

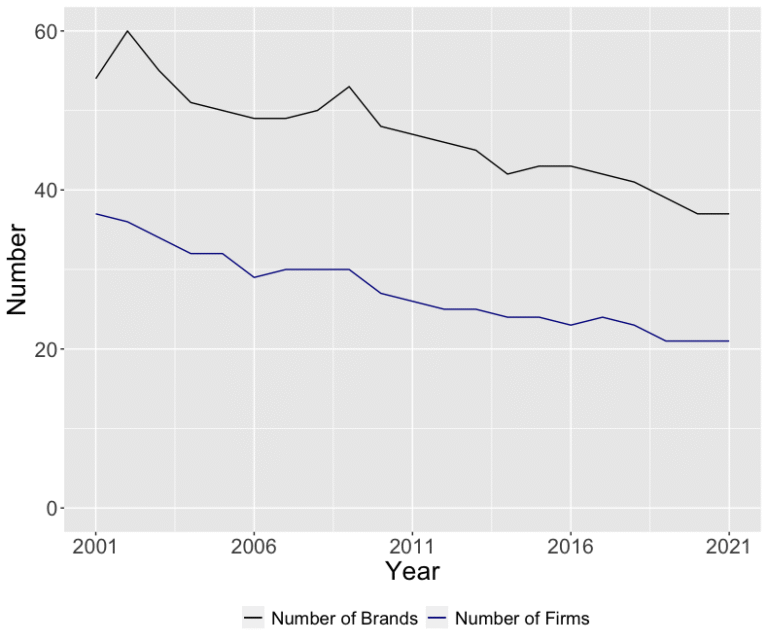

An assumption made by The Price of Over-Regulation is that competition in the Canadian auto insurance industry remains competitive. If the industry was to become too concentrated a more flexible premium rate adjustment policy could be abused. The C.D. Howe paper rightly points out this risk. However, competition in auto insurance has quietly been going away for decades, with more mergers on the horizon. Figure 1 shows the number of brands and firms operating in Ontario each year from 2001 to 2021. Here brands refer to the name brands you see when shopping for insurance such as Intact, Belair Direct, Trafalgar, Novex, or others. However, many firms like Intact own multiple brands, so while you may see 55 options in 2001 just know they are owned by just 38 firms. All the ones we just mentioned are owned by Intact. As Figure 1 shows, both the number of brands and the number of firms are falling. From 2001 to 2021 the number of firms operating in Ontario fell by 45%. The decrease in the number of firms have been driven by merger and acquisitions by Canada’s largest insurers. An example of which is that in 2020, Intact bought Royal Sun Alliance and the merger was completed in 2021. The Intact RSA merger at the auto insurance level represents one of largest increases of concentration in the industry in decades. Then looking ahead, just this March Definity (formerly Economical) announced the purchase of Travelers, which would see the 6th and 12th merge to become the 4th largest property insurers in Canada. Definity has publicly stated their plans to grow through future mergers. With consolidation front of mind for Canada’s auto insurance industry we cannot forget that the level of competition and the needed level of oversight are linked.

An Alternative Story

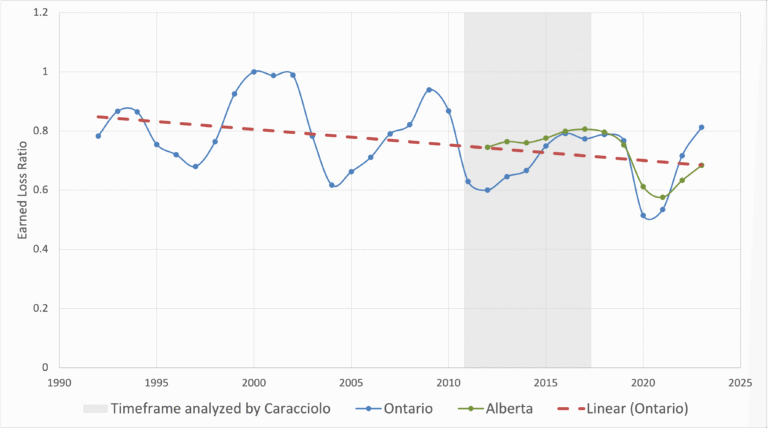

In addition to providing some additional background, we provide evidence for an alternative to what The Price of Over-Regulation concludes. Below, we offer some context and an alternative story to why provinces in group 1, the “more regulated” provinces, saw premiums increase less in line with claim costs from 2011 to 2016. Specifically in 2010, the government of Ontario changed the regulations as to the amount firms had to pay out for bodily injury accidents. By 2011 the total claims paid out by Ontario’s auto insurers and other costs associated with those claims dropped 24%. Figure 2 graphs the earned loss ratio from 1992 to 2023 in Ontario and 2012 to 2023 in Alberta. The earned loss ratio is the sum of the total claims and the costs associated with those claims (think lawyer fees) divided by the total value of premiums collected (or earned) in a year. An earned loss of one in 2000 would indicate that for every dollar collected in premiums the firms spent one dollar on claims or claim related expenses, while a ratio of 0.6 in 2004 would indicate that only 60 cents of every dollar collected in premiums were spent on claims or claim related expenses. As claim and claim related costs account for the vast majority of a firm’s overall business costs we can think of the earned loss as a measure of profitability

As Figure 2 shows, the earned loss ratio dropped drastically from 2010 to 2011, meaning that while claim costs fell, premiums did not fall with it. We can also see the impact of the regulation by looking at Alberta’s earned loss ratio around the same time. The ratio is lower in Ontario even through all the major firms in Ontario are also the major firms in Alberta. The result of the bodily injury was a huge windfall of money for the auto insurance industry as they collected the same premiums while having much lower costs. In my own working paper which analyses this policy in greater detail, the auto insurance industry in Ontario collected an additional $16 billion in premiums from the policy change from 2011 to 2021. This excludes the additional billions in premiums from the lower accident rates during COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021.

It is here, as a result of the Ontario government’s legislative change to limit bodily injury claims, where an explanation for Ontario’s premium growth in the years analyzed by the C.D. Howe paper may lie. Since firms were experiencing a higher profit margin than before, they could not increase premiums as quickly as claims from 2011 onward as the regulation tried to hold the industry to a modest profit margin. This can be seen in the rising earned loss ratio from 2011 to 2016, as a higher ratio year over year means claims and claim costs rose faster than premiums. Furthermore, when we consider the full available timeline, we can see that the earned loss ratio is cyclic. Regulation changes or other trends drive fluctuations in the earned loss that take years to revert to the mean. If the paper was to isolate a different six-year period like 2000 to 2006, they may well conclude that Ontario’s regulatory controls lead to greater profitability for insurers, and not less. In fact, the board trend line for Ontario shown by the red line in Figure 2 suggests that overall, the earned ratio has slowly fallen, meaning that on average the industry has gotten more profitable in the last 35 years.

In Summary

The paper published by the C. D. Howe Institute advocates for less pricing regulation to allow the Canadian auto insurance industry to be flexible in an ever-changing world. We have outlined however that there is much more to pricing regulation than just weather or not you need prior approval. Quick turnarounds, multiple updates every year, and the allowing of consistent profit margins is less regulated than a nonprofit, once a year change environment, whether or not you need to wait a few months to implement your new prices. The paper was right, we do live in a world of change, but that includes rising concentration that needs to be monitored, and we require both historical and current data to do so effectively. There is even more to say about this paper and auto insurance in Canada more broadly. From competition in auto insurance being more local than we think, dependent on consumer preferences and local firm presence, to brokerages and their slow integration with the firms whose products they sell. So, we should and intend to continue to talk about auto insurance regulation in Canada, and its benefits and drawbacks to the public, as there are more pieces to this puzzle.